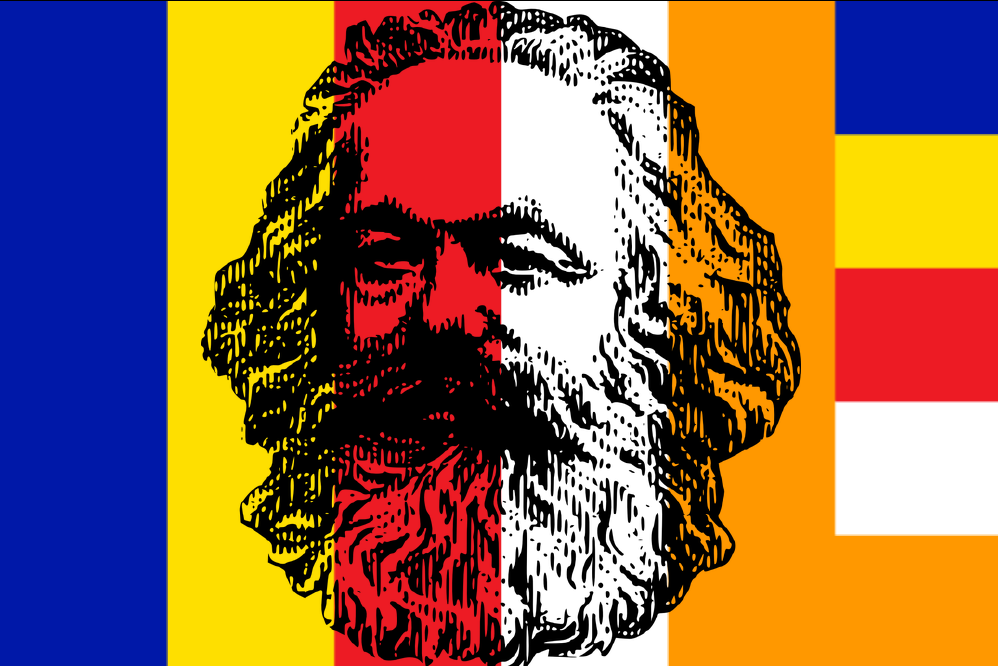

Liberation for All Beings: Marxist-Buddhist Considerations and Possibilities

tetralemma108

Introduction

Buddhism and Marxism have historically been described in terms of conflict, and it is not difficult to see why this is the case. In the first place, there is the antagonistic relationship between communism and religion, and specifically between figures such as Mao, Pol Pot, and others and the Buddhist institutions of their respective countries which they brutally repressed. There is also, of course, Marx’s famous quote that “religion is the opiate of the masses.” It is not the thesis of this essay to suggest that Marxism, in its entirety and every doctrine, contains no contradictions with Buddhism. Rather, this paper aims to prove that a synthesis of the core tenets of Marxist historical analysis and political philosophy with the religion of Buddhism is not only possible, but that these two systems of thought contain startling parallels, and study of the one by adherents of the other will be enriching to both traditions.

In discussing Buddhism, it is important to provide a caveat that Buddhism is not a monolith but a tradition with a much wider philosophical umbrella than, for example, Christianity. It is more appropriate to speak of Buddhism’s plural than of a religion simply called Buddhism. This being said, this essay will predominantly use excerpts from the Pali Canon, held sacred not just by Theravada Buddhists but also by Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhists who refer to this set of scriptures as the Agamas. Certain quotations from Mahayana scriptures will also be used, but these are largely unobjectionable even to Theravadins.

The first part of this essay will concern the areas of Buddhist scripture that present explicit political and societal instructions. Three case studies will be used to make the case that Buddhist teachings align well with the Marxist vision of a revolutionary and post revolutionary society. Firstly, the responsibility of employers in the Sigalaka Sutta will be compared with Marx’s WageLaborandCapital. Next, the monastic sangha will be examined in its similarities to a classless and moneyless post revolutionary society. Finally, the role of the state in Marxist texts will be measured against the Buddhist “wheel-turning king” or chakravartin (Pali: cakkavatti).

In part two, the theoretical underpinnings of Marxist analysis will be shown to parallel Buddhist philosophical doctrines, beginning with a comparison of Buddhist ontology and phenomenology with the foundational Marxist idea of dialectical materialism. Secondly the Buddhist source of suffering, trshna (Pali: tanha), or clinging, will be considered in light of commodity fetishism. Lastly, Duḥkha(Pali: dukkha) or inherent dissatisfaction will be connected with capitalist alienation.

The third part will consider the doctrines of Buddhism and Marxism that appear to be in contradiction, and determine whether they can in fact be reconciled. Its first section will acknowledge the Marxist understanding of history, and the ways in which the time of the Buddha had different material circumstances than the modern age, presenting a possible explanation for discrepancies between Buddhist teachings and Marxism. Next, the question of violence in Marxism and Buddhism will be shown not to be as different as one might believe at first. This part will finish with an admission of certain irreconcilable differences, but affirm that synthesis remains possible.

This essay will conclude with certain personal speculations as to the desirability of Marxist-Buddhism playing a significant role in the planet’s future, and to the lessons that the present analysis has to teach both Marxists and Buddhists both today and going forward.

Glossary

Buddhist Terms

Duḥkha: Sanskrit word referring to the dissatisfaction in all existence (universality of suffering) Trshna: Thirst, or clinging– attachment that ignores the reality of non-self and impermanence Anātman: Non self, the belief that there is no demarcation of selfhood and other

Shunyata: Emptiness, any one object or phenomenon is meaningless on its own and without self

Karma: The unfolding of the laws of cause and effect, including on a moral level

Sangha: Community of Buddhist disciples lay and ordained

Pratitya-Samutpada: All phenomena depend on other, prior phenomena, dynamism

Sutta/Sutra: Individual Buddhist Scripture Chakravartin: Just and universal monarch Vinaya: The rulebook for monks

Anitya: Nothing lasts forever

Yogacara: Sect that believes all phenomena, even karma, depend on consciousness

Dharma/Dhamma: The Buddhist teachings

Marxist Terms

Bourgeoisie: People who make money by owning (a factory, business, stocks, copyrights)

Means of Production: What is owned by the bourgeoisie and used to make wealth (ie factory) Private Property/Capital: The means of production privately owned

Proletariat/Workers: People who make money by working Revolution: Seizing of the means of production by the proletariat

Commodity: An item that is assigned a price

Commodity Fetishism: Reifying the price assigned to a commodity

Alienation: The worker does not own their product (auto worker doesn’t own the car) Capitalism: Rule of bourgeoisie of the proletariat

Leftism: Opposition to capitalism

Communism: Collective ownership of the means of production Marxism: Specific brand of communism created by Karl Marx

Wage: The minimum amount of money an employer must pay to keep a worker

Part One: Politics and Praxis

Wage Labor and the Sigalaka Sutta

The most straightforward presentation of Buddhist social teaching is perhaps the Sigalaka Sutta, a part of the Pali Canon’s Digha Nikaya, the body of long scriptures. It recounts the story of a young man, named Sigalaka, who seeks the Buddha’s advice on how he can follow his late fathers instructions to “worship the directions” of which there are six, the four points of the cardinal as well as the zenith (up) and the nadir (down). The Buddha then preaches that each of these six directions is representative of a relationship between oneself and the ones around him. Specifically, the north is representative of one’s friends, the east one’s parents, the south teachers, the west spouses, the zenith ascetics, and the nadir workers. It is this last category of the nadir that is the present concern, and it is prudent here to quote the Buddha at length: “There are five ways in which a master should minister to his servants and workers as the nadir: by arranging their work according to their strength, by supplying them with food and wages, by looking after them when they are ill, by sharing special delicacies with them, and by letting them off work at the right time. And there are five ways in which servants and workers, thus ministered to by their master as the nadir, will reciprocate: they will get up before him, go to bed after him, take only what they are given, do their work properly, and be bearers of his praise and good repute. In this way the nadir is covered, making it at peace and free from fear.”

Here the Buddha presents a rather lengthy list of responsibilities that an employer owes to their employees. It is necessary, in order to incur skillful karma, that employers provide to all their workers food, medicine, and time off, in addition to their wages, and without assigning work beyond their capability. These are requirements that remain unmet for many workers in the developed world, to say nothing of the global south, therefore the current state of the economy is one condemned by the Buddha.

Additionally, the term “wages” warrants further examination. Karl Marx uses this term in a very specific way, defined in his 1847 lecture WageLaborandCapital. Herein Marx states that the wages, which are “the cost of labor power,” will be determined by “the cost required for the maintenance of the laborer as a laborer, and for his education and training as a laborer.” Clearly, this is not what the Buddha is referring to by the Pali term “bhattavetanā” translated as “wages.” In the Marxist sense of the word, wages are the amount of money an employer is compelled economically to pay their workers in order to keep them alive and able to work, not more. Compare this with the Buddha’s instructions that “wages” be provided in addition to basic needs like food and medicine. In this case, the term must refer to money that is paid after these needs are met, meaning that the workers are actually being paid some amount of the value they create, a marked improvement over capitalism.

Despite the leftist tone of the first half of this teaching, the second is more problematic to Marxist readers. The language that is used to describe the deference of workers to their employers rings somewhat feudal in tone. This being said, the virtues that are being expressed, of hard work, not stealing, and positivity, are nothing objected to in communist literature. What is at issue here is the very existence of a “master.” First it must be noted that the identity of this master is not necessarily that of a capitalist. Even under communism, systems of management will continue to exist, and deference to leaders is not inherently a vice. Additionally significant is the historical period in which the Buddha preached, a period in which Marx would not expect communism or proletarian revolution to be opportune or even possible, but this is a topic that will be broached a few paragraphs later.

Monastic Communism

The clearest parallel to Marx’s vision of a classless, moneyless society to be found in Buddhist scripture undoubtedly lies in the instructions and descriptions of monastery life. The picture of the Buddha’s intentions for his robed followers’ lifestyle is layed out piecemeal in the suttas and sutras, and more comprehensively in the Vinaya, the compendium of monastic laws.

In the Samagama Sutta, the famous disciple Ananda witnesses bickering among Jain ascetics, and asks the Buddha how such behavior can be prevented among the Buddhist ordained community after the founder’s passing. What follows is a description of the behavior of a good monk, one who “enjoys things in common with his virtuous companions in the holy life; without making reservations, he shares with them any righteous gain that has been obtained in a righteous way, including even the mere content of his alms bowl.”

Normally, even the most ardent communist will make a distinction between private property and personal property. The former must of course be abolished, no one can own something that they have not worked for and make use of by themselves, for example a factory, a farm, an apartment building, these must be owned collectively in a Marxist society. Personal property, on the other hand, refers to one’s house, food, clothes, luxury items etc. The ordained Buddhist Sangha, taking things a step further, insists that neither is befitting a monk.

It is not the intention of this essay to argue in favor of abolishing personal property, nor would the Buddha advocate such a measure for all of society. Indeed, the monastic community relies on lay people to possess personal items so that they can donate to the monks. This being said, it is abundantly clear that monks (and nuns) are held all over the Buddhist world as the archetypal paragon of virtue and proximity to enlightenment. Most Mahayana traditions accept the possibility of lay people reaching nirvana and remaining as a lay person, but the typical arhat (awakened person), bodhisattva or Buddha is still generally understood as a renunciant in the vein of monks and nuns. Theravadins also accept this possibility, but are more strict, insisting that a lay person, at the moment of enlightenment, would proceed to live out the rest of their life as a renunciant. In the Pali Questions of King Milinda, the monk Nagasena instructs the titular king that “the state of a layman… is too weak to support arahantship.”

Ultimately then, as enlightenment is the highest good, and enlightenment is inextricably linked to a life divorced not just from private but even personal property, that the latter and especially the former are unvirtuous hindrances to awakening. Even as the complete relinquishment of personal property is impossible, Buddhists are generally to imitate a monastic life to the extent that they are fiscally and psychically able, making the consumerism and accumulation of private property inherent to capitalism something eschewed by Buddhist teaching.

The Chakravartin and the State

The next topic of relevance in constructing a Buddhist political philosophy with which to compare Marxism is the concept of the Chakravartin(Pali: Cakkavatti) or “Wheel-turning Monarch.” This figure is the ideal ruler of a nation or empire and most importantly one who supports the growth and preservation of the Buddha’s teaching. The primary Pali scripture in which instructions are given on how such a ruler should lead is titled the Cakkavatti-Sihanada Sutta, and this will be compared with Karl Marx’s thought.

In the Cakkavatti-Sihanada Sutta of the Pali DighaNikayathe Buddha tells the story of a king long ago who received sage advice from a brahman priest. In order to qualify as a chakravartin a ruler must “[depend] on the Dhamma, honoring it, revering it, cherishing it, doing homage to it and venerating it… acknowledging the Dhamma as [one’s] master.” In the earlier and later sections of the present essay, it has been and will be elaborated that the Buddha’s teaching is inherently at least somewhat communistic, and for a king to be a follower of the Dhamma would therefore require at least somewhat communistic political leadership.

Later in the same sutta, the king is instructed again to “let no crime prevail in [his] kingdom and to those who are in need give wealth.” Scripture positions redistribution of wealth as the responsibility of the state. Marx presents a similar solution to capitalism’s many injustices. In the Manifesto of the Communist Party, Marx writes that “the proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degrees, all capital from the hands of the bourgeoisie, to centralize all instruments of production in the hands of the state.” The use of state power to redistribute wealth is a responsibility of both the leader of a communist revolution and a Chakravartin. While not enough to fully identify the two, it seems that they are not mutually exclusive.

It is also worthy of consideration that Marx considers the development of communism to be an inevitable chapter in the history of humankind, and that the Buddha predicted the rise of a chakravartin prior to the coming of Buddha Maitreya. Both indicate a kind of inevitable rise of communist or communistic modes of existence.

Part Two: Theoretical Foundations

Pratitya-Samutpada, Shunyata, and Dialectical Materialism

Dialectical materialism is a cornerstone of Marxist thought from which most if not all of its other doctrines emanate. Friederich Engels defines it as “a cycle in which every finite mode of existence of matter… is equally transient, and wherein nothing is eternal but eternally changing.” This type of language will sound deeply familiar to a Buddhist reader, seeing the similarity between Engels’ words and the concepts of Anitya (impermanence), and Anātman (non-self). Indeed, the Heart Sutra is famous for stating that “all phenomena bear the mark of emptiness.” This doctrine of Shunyata (emptiness) is at the heart of Mahayana teaching and implicit in Theravada teachings as well.

Another analogy for dialectical materialism in Buddhist philosophy is the doctrine of pratitya-samutpada (dependent arising). Essentially, this tenet is the law of cause and effect, explaining the existence of another core Buddhist concept, that of karma. Between shunyata and pratitya-samutpada, Buddhism has a very direct analogy to dialectical materialism.

There is, however, a major elephant in the room regarding this comparison. Buddhism may be dialectical, but it is certainly not materialist. The Buddha was extremely explicit in his acknowledgment of gods, spirits, heavens, and hells. Ultra-idealist Yogacara Buddhists go so far as to deny the ultimate existence of Pratitya-samutpada as anything other than a mental construction that has been mistakenly reified.

There is room for reconciliation here though– even the most spiritual among us do not deny that, in the average person’s lived experience during the modern age, existence is entirely material. The course of human history, for the most part, has indeed been defined by material conditions. Marx, however, understands communism to be the end of history, just as enlightenment is the end of arising. Synthesis is possible here if dialectical materialism is understood as a contingent reality that can be escaped from through the overthrow of capital, similar to the way that Yogacarins understand karma as a highly impactful process that is nonetheless ultimately only a mental construction.

Trshna and Commodity Fetishism

After his enlightenment, the Buddha delivered his famous first sermon on the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path. Among the former, the first is that of Duḥkha (suffering) and the second is that of Samudaya (cause) namely Trshna(attachment), “the truth of the source of Duḥkha is the attachment that causes rebirth.” This last term is often translated into English as “desire” but in modern scholarship this is widely considered problematic.

Even after enlightenment, a Buddha or arhat will still feel hunger, thirst, and, significantly, compassion, all of these could be termed as desires. What awakened individuals do not experience is attachment, they may be hungry and want food, but they will not suffer for lack of food, they may desire the well-being of their fellow creatures, but will not suffer only because they do. It is also important to note that enlightened ones do not desire after frivolous consumer goods, but only that which serves a purpose.

Karl Marx, in Capital, Volume One, explains that “the mystical character of commodities does not originate… in their use-value. Just as little does it proceed from the nature of the determining factors of value.” Instead, the value of commodities in capitalism is the result of “the peculiar social character of the labor that produces them.” In short, the value is not intrinsic but contrived by capitalists.

By definition, a Buddha or arhat would never fall for such a system. When considering the relationship between Buddhism and Marxism, it is telling that capitalism is constructed on the fundamental obstacle to enlightenment. The Buddha and Marx both recognize the harmful effects of Trshna in as many words, and for similar reasons.

Duhkha and Capitalist Alienation

The truth of Duḥkha has already been mentioned in the preceding passage, and trshnaas its cause. In the Paticca-Samuppada-VibhangaSuttathe Buddha divides this process into a set of twelve causal links, beginning with ignorance and ending with the suffering of aging and death. Ignorance here refers to “not knowing Duḥkha, not knowing the origination of Duḥkha, not knowing the cessation of Duḥkha, not knowing the way of practice leading to the cessation of Duḥkha”. In short, it is an unawareness of Buddhist teachings that ultimately cause the world’s suffering.

Buddhists universally hold the truth of Anātman, the fact that there is no self. In the Mahayana, this doctrine is further developed into one of non-dualism. The HeartSutra preaches that “in emptiness, body, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness are not separate self entities.” The same non-duality applies to cause and effect, to the six senses, and, implicitly, to everything in this universe. For any one entity to be separate from any other would require a self, and belief in a self is inherently a form of attachment to whatever entity is assigned selfhood, and thus a cause of suffering. A Buddhist who upholds the goal of enlightenment is therefore instructed not to conceive of a subject and object duality.

In Karl Marx’s Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, he describes how, under capitalism, “the worker becomes a servant of his object.” Labor, a process that in Buddhist terms could be defined as the interplay of mental formations and form itself, is part of the “intrinsic nature” of an individual, is presented as “an object, an external existence… outside him, independently, as something alien to him,” by the capitalist class.

In summary, private ownership of the means of production forces duality of subject and object onto the working class. This duality is one cause of the delusional belief in selfhood, therefore of attachment, and in the end, of suffering. If workers understood the unity of themselves and their labor, capitalism would be impossible to sustain. It is in the interest of capital owners to saturate the culture with ideas that reinforce this mistaken duality, and the aim of both Marxists and Buddhists to dismantle those same concepts.

Part Three: Apparent Contradictions

The Marxist Understanding of History

As much as the preceding words have established the similarities between Buddhism and Marxism, certain readers may still be hesitant to deem the two schools compatible and complementary. In fairness, certain apparent contradictions remain. As socialist as the Chakravartin may be presented, he is still a king, a position condemned by communists. In the previous section regarding this topic it was argued that the Chakravartin may represent the leader of a proletarian revolt, only referred to as a king for convenience. The same can be said of the landowner in the Sigalaka Sutta, and in various other cases- imperfect terms of convenience used by the Buddha can be considered mutable and adapted to a communist context. However, even if this argument remains unconvincing, there is still a possible reconciliation between Buddhism and Marxism via Marx’s conception of history.

Famously, in the Manifesto of the Communist Party, it is written that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” This history, passing from Ancient, to Feudal, to Bourgeois and finally to communism is a natural process, each phase is necessary in producing the material conditions that create the next. “The modern bourgeois society… has sprouted from the ruins of feudal society,” and in turn, “the bourgeoisie itself… furnishes the proletariat with weapons for fighting the bourgeoisie.” Capitalism creates the necessary level of industrial development for communism, as did feudalism for capitalism and so on.

With this acceptance of the necessity of each age of history, the Buddha’s reluctant acceptance of monarchism and private land ownership appears justified. The fact that the Buddha provided guidelines for the ethical behavior of kings and landlords more than two millennia ago would not be an issue for Marx, insofar as it does not follow that were the Buddha to preach today that he would continue to support monarchies. In fact, based on the underlying principles of the Buddhist social and metaphysical doctrines, the only context in which these statements can be understood is as either already referring to communism or being specific to their historical era.

Compassionate Violence and Revolution

The first precept instructs the lay followers of the Buddha to refrain from taking life, even that of animals let alone human beings. Conversely, the Manifesto calls for “the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions,” inevitably resulting in the use of lethal violence. Attempts at reinterpreting the first precept are not unique to Buddhist radical leftists; each of the many states in history that have adopted Buddhism have had to negotiate how this rule is to be treated.

For some, there are no exceptions, killing is forbidden to all Buddhists, but this is not necessarily a majority position. Firstly, while violation of the precepts generates negative karma, there are ways to compensate for this through Buddhist practice. One example is presented in the Questions of King Milinda, a text that has been consulted in the first section of this essay wherein a great king makes doctrinal inquiries of a notable monk named Nagasena, resulting in a kind of Buddhist catechism especially in the Theravada world.

In the second verse of the Questions’ seventh chapter, King Milinda calls into question the belief that “a man who has lived an evil life for a hundred years can, by thinking of the Buddha at the moment of his death, be reborn among the gods.” Nagasena responds with an analogy, stating that although “a tiny stone” could not “float on water without a boat… even a cartload of stones would float in a boat.” In essence, Nagasena is explaining that the negative karma of bad deeds can be mitigated if performed by pious individuals who have made a “cushion” or “boat” of positive karma.

This teaching must have been a great relief to figures like King Milinda who, in spite of their moral convictions, would inevitably have to use violence in some cases to maintain order for the greater good. A similar rationale might be applied to Buddhists who are convinced by the Marxist argument that revolution is a moral necessity.

While the Questions describes the mitigation of bad deeds, the Mahayana Upayakausalya Sutra goes further and describes how a deed that is negative karmically, and thus “bad” and a violation of the precepts, can, from the perspective of the Bodhisattva path, be ultimately a good deed. In this text, the Buddha tells a story of one of his past lives as the captain of a ship. On that ship were a great many sailors, one of whom is a robber with the intent to kill everyone on the boat.

The future Buddha thought to himself “there is no means to prevent this man from slaying the merchants and going to the great hells but to kill him… if I were to report this to the merchants, they would kill and slay him with angry thoughts and all go to the great hells themselves… If I were to kill this person, I would likewise burn in the great hells for one hundred thousand eons because of it. Yet I can bear the pain of the great hells, that this person not slay these five hundred merchants and develop so much evil karma. I will kill this person myself.”

In this case, the future Buddha’s act of killing was in fact one of incredibly deep compassion and self sacrifice. The text goes on to recount that, because of his willingness to suffer in the hells in order to prevent the robber and merchants from experiencing the same fate, the future Buddha was never condemned to hell at all but actually shortened the length of time preceding his enlightenment. It is not difficult to imagine how this same rationale might apply in the application of revolutionary violence by proletarian leadership.

With all the preceding being said, it is clear that there are ways to reconcile Buddhism with violence, but there are significant caveats. Firstly, that violence can never be gratuitous and be treated only as a deeply regrettable last resort. Secondly, and more importantly, that violence only be performed by the spiritually mature, so as to avoid the horrible consequences of negative karma.

Irreconcilability and Essence

There remain certain points on which Marx and the Buddha disagree. For example, although dialectical materialism can be understood in terms of pratitya-samutpadaand Yogacara karmic frameworks, it would be dishonest to suggest that Marx had these explanations in mind. Marxism denies the existence of the supernatural, and Buddhism affirms it. Similarly, Marx encourages the abolition of the family unit (albeit in a somewhat unclear manner), while the Buddha praises filial piety. Many more such cases could be presented.

In spite of these differences, on which there can be no reconciliation, it remains the case that Marxist-Buddhism, is possible as a coherent ideology. For synthesis to be possible, it is not necessary that there be no contradictions between two systems of thought, but only that the essence of each are compatible. Marxism is not defined by disbelief in the supernatural, or its critique of the family, but rather by its analysis of human history, social and economic relations, their impact, and their resolution. Buddhism, on the other hand, is defined by its belief in supernatural forces. For this reason, it can be said that Marxist-Buddhism is possible, but Buddhist-Marxism is not. This synthesis is possible, and indeed probable and comfortable, but it is Marxism that must compromise and conform to meet Buddhism.

Conclusion

The foregoing few pages have established the parallels that tie Buddhist political thought and metaphysical theory to the ideas of Karl Marx and his successors. Indeed, if one were to construct a political philosophy in good faith, based on Buddhist principles, and keeping in mind the ways that history has altered the appropriate modes of government in production, the resulting ideology would very closely resemble Marxism, and many of the concepts that such an intellectual project would produce have already been expressed in the existing communist literature.

Some may object to the comparison between Buddhism, a religion, and Marxism, a political and historical philosophy. The comparison is not a direct one, and this has been briefly alluded to in the directly preceding section on irreconcilability and essence. Marxist-Buddhism is possible, and Buddhist-Marxism is not. Marxism’s denial of the supernatural is not a core belief, Buddhism’s affirmation of the supernatural is, so for this reason Marxism must conform to

Buddhism for both to retain their identities in a syncretized system of thought. Additionally, the fact that Buddhism is a religion, and Marxism only a philosophy, further indicates that Buddhist principles must take precedence where there is contradiction.

The fact that Marxist-Buddhism is more Buddhist than Marxist is not a shortcoming from a communist perspective. Marxism’s fatal flaw lies in its absence of a clear moral and spiritual framework. When revolution is presented as an inevitable end point to history based on groups of people acting in self interest, it is easy to be corrupted and co-opted, as has happened frequently in the history of Marxist revolutions. The introduction of spirituality and transcendent ethics to Marxist revolutionary politics lends a moderating influence to a time with great potential to violence, and a divine impetus and religious fervor that can sustain the proletariat in its struggle for the abolition of class.

Marxist-Buddhism has taken influence from and has further lessons to be learned from Christian liberation theology and other variations of the religious far left. This being said, Buddhism is a religion uniquely suited for the revolutionary project. As admirable as the various aspects of Christianity and Islam are, both are fundamentally not “of this world” so to speak. Suffering is an inherent aspect of life in a fallen world and can often be a test from God. The end of suffering is something to be attained after death. Judaism is an ethno-religion that is not evangelistic, and while there is a rich history of Jewish leftism, Judaism by its nature is not a religion that will compel the global masses toward anything, because it is not for all people. Hinduism is, by and large, not any one religion, and thus cannot be spoken of with any absolute terms. This being said, there is no small feudal element to Hindu scripture with its varna or caste systems, a substantial national and ethnic dimension, and general disorganization as one Hindu may believe very different things from their next door Hindu neighbor. Sikhism is something of a

contender, but in the opinion of this author has less compelling philosophical foundations than Buddhism. Confucianism lacks a sufficiently mystical and populist element, and Daoism lacks organization and uniformity. New Age religions such as the Neopaganisms or Wicca are, in many cases, either predatory cults or at best roleplay.

Insofar as communism is intended to give all people equal opportunity, to ensure that all people are capable of making a comfortable living, and to prevent any one person or group from hoarding inordinate amounts of luxury goods, it intends to diminish the impact of Trshna, and by extension of Duḥkha. Collective ownership of the means of production is the first step to the kind of social harmony present in a monastery.

More pages could be filled with reasons for the unsuitability of different religious traditions to radical left wing thought (relative to Buddhism). Ultimately, Buddhism is one of the only religious systems that refuses to take the problem of suffering lying down. Suffering is not inevitable and can be conquered. Suffering is not justified as being a test, as being ultimately a good thing, or as being an unavoidable part of life. It is an injustice to be conquered. Communism is similar, in its refusal to accept the capitalist, feudalist, or fascist truism that a repressed underclass is an unfortunate necessity. Even more than their theoretical and political affinities, it is the insistence on the end of all suffering that unites Buddhism with communism.

It is one of the great missed opportunities of history that the inherent affinity between Buddhism and Marxism has been ignored by many in the latter camp. This misperception has led to incredible violence against Buddhists by communist governments in places such as China and Cambodia where the dharma once thrived. The history of capitalism is wrought with atrocities, and indignity is inherent to its nature, but there can be no denying that brutality has also occurred in the name of communism. One can imagine that, with the introduction of Buddhist ethics, many of these pitfalls may have been avoided.

In conclusion, the proliferation of a Marxist-Buddhism synthesized as above presents a more compassionate, sustainable, and spiritual variety of communism. Although this essay is by no means exhaustive or sufficient for the establishment of such a political system, it is my intention that it furthers the cause in some small way of liberation for all beings.